As Published in the Irish Times 17/12/19

It is an odd thing to grieve for someone who is still alive.

Nothing has ever resonated with me more as when I heard Alzheimer’s described as the long goodbye. The grief with the illness is cruel and unforgiving.

A kind of limbo grief.

I feel like I don’t have a right to see something that reminds me of my mother and sit down and cry my heart out. Like when I got married and she didn’t understand what was happening, and doesn’t know her only child finally settled down after her spending years telling me to do just that.

You don’t feel like you have the right to this grief.

Because she is alive. I can see her. I can touch her. She was at my wedding.

Except it isn’t my mother.

I can tell her I had a walnut whip today and it was delicious and she will smile, childlike. But she doesn’t know what I am saying. Every now and then she will look at my wedding ring and admire it, but not know it is her daughter’s ring she is admiring. Mum sometimes knows she has a daughter, but not that I am her. She sometimes knows she has a husband but often asks my dad where he is.

Each time grief stabs at both of us.

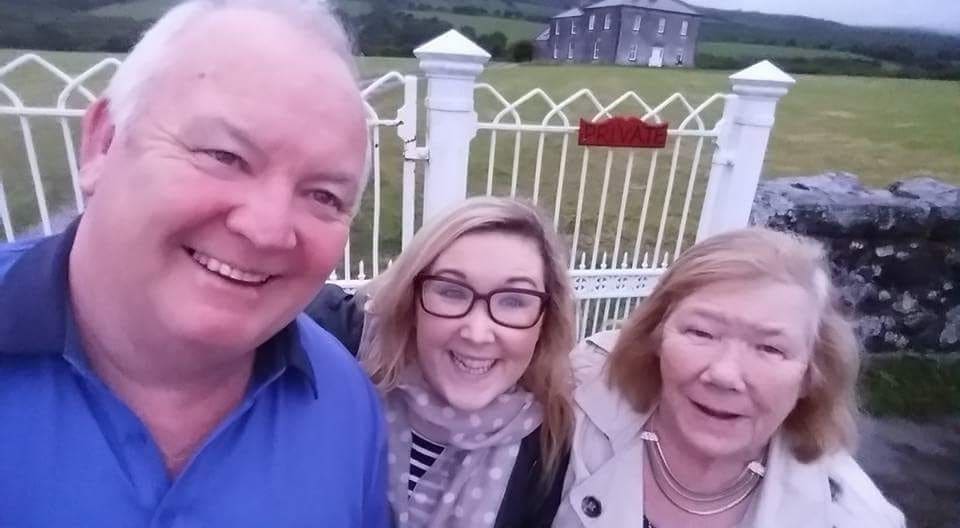

My mother has had Alzheimer’s for more than five years.

That is a five-year goodbye.

The first sting of grief was the shock of her diagnosis. But that first year she just seemed a little more forgetful, a little bit more irritable. A little bit more scatty, but still my mother. Still her devilish tricks. Still her wonderfully wicked sense of humour. Still had her vanity. Still telling me to settle down and have some babies.

Initially, we were lulled into a false sense of security.

The next year, she seemed less my mother.

And the year after.

Slowly, she was stripped of those personality traits that made her my mum.

The past two years, Alzheimer’s has stolen her.

Every now and then, my dad and I will recognise glimpses of that devilish way of hers, but they are mostly gone.

It was her loss of vanity that was almost the biggest stab of grief. The first time I picked her up from her nursing home I was gung-ho: “not letting my mother go back to that place full of old sick people – she would hate it”.

Then I realised she didn’t hate it. She fitted in with the old, sick people. She actually seemed to like it. That was a blow of grief. And each time that sharp pain that takes your breath away reminds you that this is not a quick process. There are plenty more to come.

I have tried to prepare myself for every stage of the disease and the inevitable stab of grief. But it doesn’t get easier. I hear people who have lost their own mother and empathise, but feel like I can’t because physically I haven’t lost mine.

It is a weird limbo. It is like a boxing match you thought you were prepared for but weren’t.

But I have lost my mother. And in many ways, I can hear her saying, “we just have to get over it and keep going”.

What I would do to argue with her again, and her to tell me she doesn’t like my dress or hair.

We are from Galway and Western Alzheimers, which provides care for people with Alzheimer’s in the west of Ireland helped us find out what our rights are with mum, and they provide long-term care which she is currently in.

Christmas is a hard time for grief and the support for carers and those who are left behind from Alzheimer’s. While there are supports for carers, these supports are limited, especially in rural areas and need to be increased so they are easily accessible right across the country.

Especially at this time of year.